The Maker Mindset

I can remember a time when tinkering in a shop was considered a bit nerdy.

But I literally grew up in a shop.

Of course we had a workshop at the ranch, but also in school where our Ag department had all the tools painted in outlines on the wall like a murder scene.

The ones who spent hours bent over half-finished contraptions or early prototypes were those folks who just couldn’t resist peeking under the hood. Those who made things weren’t celebrated outside small circles, and they sometimes got puzzled looks from casual observers.

Yet these same folks would see a broken toy car or a dismantled radio and think, “Let’s see what I can do with this.”

There was a genuine sense of curiosity that refused to stay in a neat box.

I’ve always been one of those people.

I just like to build things.

That can be electronics, bots, or even companies.

“Maker” is the best label I can pin on myself because it pretty accurately describes the inclination to piddle in a shop and produce something tangible.

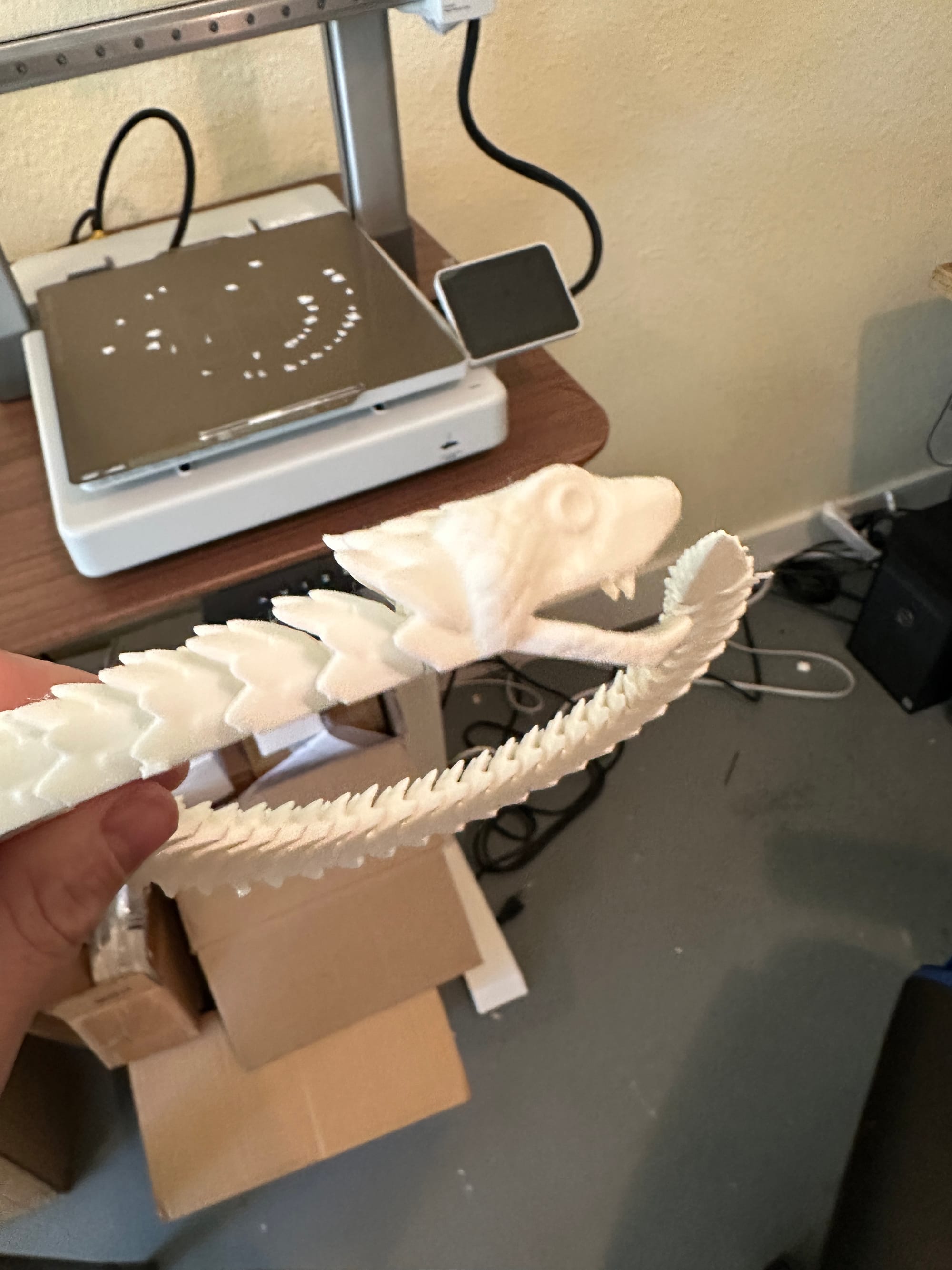

When I say “shop,” I’m talking about a slightly chaotic place filled with 3D printing spools, random bits of electronic circuits, well-worn wrenches, and maybe a dusty coffee mug that’s been sitting around since who-knows-when. Or it's my well-worn laptop with missing letters on the keys.

(I'm not quite sure why I type so many a's.)

That’s my playground.

That’s where I feel the most engaged.

A while back, I took that maker's spirit and stretch it into digital territory. So I learned a few coding basics, tried building bots, and even fiddled with CSS.

The motivation wasn’t about a flashy alternative career path. It was simply the same maker's impulse: building something that serves a purpose, whether physical or digital.

This drive, though, isn’t special to just a handful of us.

Every person I meet has a spark of curiosity about the world. I’m convinced it’s part of what makes us human.

We want to know how things work.

We read the news, change careers, or pick up new skills because our mind wants fresh input.

Some folks might not call themselves “makers,” but scratch below the surface, and you’ll find that same spark. The question often comes down to whether we reach the stage of action.

That’s the deciding factor.

Some folks get a creative idea, but it stalls at the concept stage. Others jump right in, possibly failing a hundred times before making something that functions.

That leap from idea to execution is where makers live.

I’ve heard the assumption that only certain people have this tinkering trait, but that doesn’t ring true.

Curiosity is a near-universal trait.

The difference might lie in a maker’s attitude toward experimentation and failure.

The more you spend time in this space—be it a garage or a digital workshop—the more you realize the number of unsuccessful projects far outweighs the ones that turn out well.

It’s normal to see a stack of half-melted plastic prototypes, code that crashes your browser, or half-finished drone frames. Those mishaps rarely see the light of day, and you won’t find them headlining any social media feed.

Yet each one is an essential learning step.

If you look at any YouTube maker channel, you’ll see polished end products.

Hidden behind that polished piece are countless misfires, broken pieces, and versions that got no traction. That’s what being a maker is: embracing the possibility of failure and doing it anyhow.

Today, I want to talk about being a maker - and how exploring this curiosity can inspire executives to become AI savvy.

THE MAKER MINDSET

Before diving deeper, let’s talk about the maker movement.

It’s not some fringe club, nor is it a new idea.

The movement is a cultural shift that pushes each of us to be creators rather than just consumers.

It’s about picking up a soldering gun instead of buying a pre-made gadget. Or grabbing a couple of 3D design files and printing your own replacement parts instead of ordering them off the shelf.

There’s a beauty in learning through doing. That’s why so many people refer to it as hands-on learning.

Dig in, and you'll immediately see results (or problems) to adapt to. You don’t have to wait for a structured course. You watch a tutorial; you read a couple of forum posts, or you chat with friends who’ve tried it. Then you test it out, see if it actually works, and learn from the experience.

That spirit of self-sufficiency is one element that draws me to this culture.

Instead of relying on some massive corporation for every little need, you can come up with your own projects that fit your exact requirements.

Granted, some folks prefer the convenience of buying finished products, and there’s no shame in that. But for those with the maker impulse, building something with your own two hands (and maybe a bit of software) provides a distinct feeling of satisfaction.

You know exactly how your item came to be.

You understand the design decisions, the limitations, and the trade-offs. It’s your build, from sketches on a napkin to the last parameter in your software.

Community is another massive piece of the puzzle.

Open source hardware shops, maker fairs, and local meetups welcome people of all skill levels to share knowledge, borrow specialized tools, and get feedback. Where once you might have struggled to find a certain part or piece of advice, now you can hop online or drop by a local maker club to solve your hurdle.

That kind of support helps people take on projects that might otherwise seem impossible. And if a seasoned maker sees you struggling with a circuit or a tricky code snippet, they might show you a trick that ends up saving you days of frustration.

Here’s the kicker: While there’s a strong thread of curiosity running through the maker movement, the real hallmark is the focus on execution.

Curiosity by itself might look like reading a random blog post or daydreaming about a new phone app idea. Makers push that further. If something sparks their curiosity, they build it—or at least attempt it.

The result might not always be usable, but the attempt is the magical step. It’s that willingness to face a high possibility of failure and still dive in. After all, behind every neat 3D-printed drone or custom-coded chatbot, there’s someone who said, “Let’s see if I can make this work,” even if the odds were fuzzy.

THE SHIFT TO DIGITAL

Over the past couple of years, I’ve blended that hands-on approach with digital undertakings.

Coding once felt inaccessible, like it belonged to a certain group of tech gurus. But the barriers have been knocked down.

Now there are tutorials everywhere, free code editors that run right in a browser, and communities ready to guide you through your first “Hello, world!” script.

Some of my projects involved building simple bots that automate tasks or chatbots that can respond to basic queries. Every time I got something working, it was like seeing a physical object come to life—except it existed in a digital context.

This transition isn’t just about code. It’s also about how hardware has become cheaper and more user-friendly.

A couple of decades back, a standard 3D printer and the software needed to run it were complicated and pricey. It demanded specialized knowledge.

Today, you can order a modest 3D printer delivered straight to your door and start experimenting within hours. The software has gone from commands typed on a black screen to user-friendly interfaces that let you drag-and-drop designs, tweak infill parameters, and hit print.

Laser cutters once belonged in large shops with big budgets. Now, you can have a small laser engraver in your garage for a fraction of what it once cost. You can watch a YouTube tutorial that walks you step by step, and by the end of that same day, you might etch personal designs on wood or acrylic.

Aerial photography was once an art that demanded either a hot-air balloon, a plane, or a helicopter. Now, you can zip down to a local store or place a quick order online for a DJI drone and capture sweeping footage you’d once only see in professional films.

We’re witnessing this explosion in the digital environment, too.

Websites, once the domain of specialized coders, are now made by everyday folks using drag-and-drop platforms. You can bolt on a chatbot to your site with minimal hassle.

That’s not to say actual coding is no longer relevant. It’s still the foundation for all these tools, but the average person can now craft a digital experience without needing extensive programming training.

This is part of what’s fueling the maker movement’s push into the online space: the threshold for entry has never been lower, and the possibilities for personal creations keep growing.

MAKERS IN PRACTICE

Sometimes it helps to see actual examples of how curiosity and execution can shape outcomes.

Let’s start with someone building drones. A decade ago, that would have sounded complicated—soldering flight controllers, balancing blades, and picking the right motors. Today, kits come with color-coded wires and instructions that even a first-timer can follow. Videos show you precisely how to calibrate your drone so it doesn’t bounce off the wall on its maiden flight. Once it’s up and running, you can capture footage from angles that used to be off-limits for amateurs.

If you’re a content creator, that means more dynamic shots and a chance to stand out. If you’re a small-business marketer, that might mean showcasing products in a unique manner, filming overhead tours, or giving customers a fresh perspective on what you offer.

Then there’s laser engraving.

Think of the average person who wants to personalize a set of wedding favors or brand their merchandise with a logo. It’s no longer necessary to hire an outside specialist. You can order a compact laser cutter, dabble with the design in free software, and produce the entire batch in your garage.

That’s a direct outcome of how accessible the tools have become.

People’s curiosity about how to personalize items, combined with the newly available hardware, leads to small businesses that revolve around custom pieces. It can be a key marketing angle, too, since you can show customers the entire process from design to final product.

That transparency helps build trust.

Consider 3D printing as another example.

Let’s say you have a product idea—maybe a gadget that organizes cables on a desk. Instead of hiring a design firm to prototype it, you can open a free design tool, model the shape, and print it yourself. If the design isn’t quite right, you print another version with minor tweaks. This direct process stands in sharp contrast to the older method of shipping prototypes overseas or waiting weeks for a professional mold.

By the time you complete your design, you’ve learned not only how to create the piece but also what pitfalls to avoid. You know your product’s strengths and weaknesses, and that can guide your marketing message. You can speak with genuine insight, showing potential customers exactly how it works because you designed it from scratch.

MARKETING CONNECTIONS

In the marketing world, focusing on curiosity can reshape how you approach campaigns.

Perhaps you design hands-on experiences that allow your audience to interact with your product or service in an exploratory way. It might be an interactive tutorial, a challenge that invites them to design their own version, or a short quiz that reveals a hidden feature.

By inviting your audience to become active participants, you’re playing into the same curiosity that fuels the maker's impulse. After all, it’s much more compelling to grip something and see how it works than to simply hear a pitch.

In fact, let's build a quick AI tool together. Here's a short video that will show you how to use two very common solutions - Google Sheets and Perplexity - to build your own blog writer. Give it a try.

It’s also wise to remember that convenience is a big draw.

One reason maker tools have spread so fast is because they turned simpler and more affordable. Marketers can think the same way: how to reduce friction so that the curious folks can see results fast.

Maybe that means giving them a small project or a demo piece they can put together in minutes. Once they see it work, they might be inspired to do more.

That’s the same gateway many folks have taken into 3D printing or coding.

Failure tolerance is another huge insight from the maker world.

That tolerance encourages iteration.

In marketing, it can do the same. Rather than sinking all your time and money into a large campaign before seeing if it resonates, put a smaller pilot out there and see what happens. If it flops, you glean real data, pivot, and try again.

Much like a maker who prints a flawed component, adjusts a few design factors, and reprints, a marketer can test one angle, change the messaging, and test again.

DON’T FORGET THE STORIES

One of the best things about being a maker is that every finished product hides a story of how it came to be.

And those stories are gold for marketing because people connect with them. They want to know about the idea, the process, the hiccups, and how it finally reached the finish line.

So if you’re a business owner or marketer, consider weaving those real-world anecdotes into your public outreach. Show that raw behind-the-scenes process where the device malfunctioned or the code spat out strange errors. Those details help you stand out, especially in a world crowded with polished marketing assets.

Folks appreciate transparency and honesty.

If you openly show that not everything goes as planned, you’re more relatable.

Displaying a personal narrative behind a product can be more compelling than a flashy ad that presents a perfect outcome. This lines up with the spirit of the maker movement: embrace the learning curve, celebrate the breakthroughs, and share the hits and misses alike.

WHY IT MATTERS

Some folks might wonder why all this tinkering and do-it-yourself talk is relevant.

Isn’t it quicker or simpler to hire a professional?

Sometimes it is.

But exploring personal skills, even if just a bit, uncovers new possibilities. It sparks new ideas.

By learning a little coding, a little design, or a bit of hardware basics, you expand your creative potential.

Solutions to small daily problems can appear because you see them not as insurmountable hurdles, but as challenges waiting for a fix.

That mindset then spills into professional life. If you’re in marketing, you begin to think of creative campaigns. If you’re in product design, you empathize better with user experiences because you’ve had your hands in the creation process.

That endless curiosity spurs improvements in every field.

People aren’t content just watching from the sidelines.

They want to do more, test more, and discover more. And the maker movement is about harnessing that desire.

You give people the space and tools, and they’ll figure out fresh ways to address problems. Over time, this approach has led to wave upon wave of new ideas, on both small and large scales.

This is especially important to business leaders and CEOs. Here is a white paper we have put together with recommendations for executives on starting the journey on AI-forward company transformation:

WRAPPING IT ALL UP

So here we are, reflecting on tinkering in a dusty garage, stacking half-printed prototypes in the corner, or debugging lines of code until everything falls into place.

The maker movement stands for people who actively chase their curiosity and aren’t defeated by the prospect of failures.

It’s about putting in the work, messing up occasionally, and eventually bringing something real into the world—whether that something is a wooden lamp carved on a laser, a chatbot that interacts with customers, or a new piece of code that automates mundane tasks.

Marketing folks can learn a great deal from this.

Instead of throwing out polished ad campaigns that give no insight into the messy reality of how products or services are conceived, try revealing a bit of that creative hustle.

CEOs can transform their companies and leap frog competition.

Show that curiosity can lead to something tangible.

Offer tools or steps that let your audience or employees test it for themselves. Empower them to be co-creators, not just buyers and users. That approach resonates deeply because it acknowledges that spark within everyone.

We all have curiosity.

Some of us just need the right environment and enough courage to put it into action.

That’s the key point: curiosity plus execution.

The difference between a passing thought—“Wouldn’t it be neat if…”—and an actual result is the willingness to dive in and risk failing.

Makers take that plunge.

They bring each fleeting idea closer to reality.

And these days, the path is clearer than ever. Tools are cheaper, tutorials are abundant, and communities are ready to help.

Once people dive in, the results can be surprising.

The maker movement’s emphasis on hands-on learning, self-sufficiency, and community support reflects a shift in how we approach challenges.

People realize they can craft custom solutions, whether they’re physical items or digital applications. They can start small, pick up just enough coding or mechanical knowledge to get by, and refine through trial and error. None of us sees every idea through to a smashing success, but each attempt contributes to the next round of experiments. Over time, that patience and dogged persistence pay off.

Maybe you’re like me, with a penchant for rummaging in a shop. Or maybe your “shop” is purely digital—a code editor, a handful of software design tools, and a strong cup of coffee.

Either way, the best part about “making” is that it never really ends. After finishing one project, you see how it might be improved. Or you move on to a brand-new concept.

Each path fuels your curiosity and leads to another round of testing. It’s a continuous cycle of discovery.

That same spirit can transform the way we market, the way we learn, the way we lead, and the way we solve real-world problems.

It encourages each of us to look at the world around us—be it business hurdles, personal goals, or community challenges—and ask, “What can I build?” Then we head to the garage, the maker space, or the digital sandbox, and we tinker.

If it fails, we try again.

If it works, we share it.

Somewhere in between, all of that is the joy of creating. And that, to me, is what being a maker is all about.

Member discussion